Volume 69, Issue 07 (December 2017)

Cold War Revisionism Revisited:

The Radical Historians of U.S. EmpireAs a graduate student in the 1960s, I was inspired by the new science of international politics and the claim that by gathering enough data and analyzing it carefully, using the latest statistical techniques, scholars could develop an integrated theory of international politics that could replace limiting assumptions about human nature. We could study war, intra-state violence, revolution, economic cooperation, and institution-building with rigor. At last, scholars could develop a science of human behavior that would parallel the natural and physical sciences.

Based on the lingering assumptions of realism and the passion for constructing a science of international relations, two areas were subjected to specific inquiry: national security and modernization. Security studies was designed to use the tools of science to determine how nations could best defend their physical space and deter aggression. Modernization studies emphasized processes of economic development that could improve living standards, particularly through markets and democratic institutions. In the end, the American field of international politics was dominated by this nexus of realism, behavioralism (the quasi-scientific study of international behavior), security studies, and modernization.

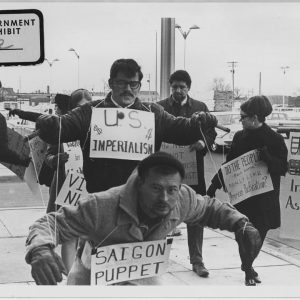

Not coincidentally, these approaches to research and education in international politics arose at the height of the Cold War. The United States was embarking on a dramatic escalation of its adventure in Southeast Asia, and defense spending was expanding such that President Eisenhower warned of a growing “military-industrial complex.” As the war in Vietnam grew more controversial, the prevailing international-relations perspectives were increasingly challenged, both in the classrooms and the streets. But for the most part, studies based on paradigms of realism, behavioralism, security, and modernization remained disconnected from broader debates about the world.

To the era’s activists and radicals, the cause of this disparity between the academic study of international politics and the social reality of the anti-war movement was obvious. The former was influenced and supported by governmental institutions, including the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency, and in the main, its theories and approaches served intellectually to justify U.S. foreign policy—from nuclear buildups and military interventions to sponsoring coups and assassinations. In sum, the midcentury American science of international politics, which shaped a generation of students, was an ideological tool serving the foreign policy of the United States and its allies.

Political Economy and Foreign Policy

Academic fields were transformed into ideological training grounds in support of the United States’ mission in the world. In history and social science, new scholarship portrayed an American politics, history, and society founded on pluralist democracy rather than political elitism, consensus-building rather than class struggle, and groups, not classes, as the basic units of society.

Indeed, in the 1950s, some realists represented the most “radical” of critics of U.S. foreign policy. While they did not highlight economic interest, the pursuit of empire, or overreaction to the Soviet threat, they did argue that U.S. national interests had to be defined more carefully in security terms. They challenged the view that moral purpose and global vision should or could guide foreign policy. Theorists such as Morgenthau claimed that international relations should be motivated by needs of national security, not some grand campaign against international communism.

At the same time, however, a handful of historians began to challenge these dominant narratives. In particular, the history department at the University of Wisconsin encouraged young scholars to examine the economic taproots of U.S. foreign policy. In 1959, the university’s most influential historian, William Appleman Williams, broke new ground with The Tragedy of American Diplomacy. His students and others began to challenge reigning orthodoxy about international relations and the historic role of the United States in the world. Williams documented the rise of an American empire that expanded after the Civil War, while other historians began to conceive of the conquest of the North American continent as part of an empire-building process founded on the slaughter of millions of native peoples and the seizure of a large section of the landmass of Mexico. Still others studied the kidnapping and enslavement of millions of Africans as central to the construction of the Southern cotton economy, and ultimately to the global capitalist system.

In The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, along with The Contours of American History (1961) and The Roots of the Modern American Empire (1969), Williams located the origins of U.S. imperial expansion in the rise of agricultural production and the need for a growing economy to find markets overseas, particularly after domestic outlets had been capped with the closing of the “frontier.” Drawing on Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis,” U.S. leaders believed that a new, global American empire was needed to sell products, secure natural resources, and find investment opportunities.

The rift between realist thinking and the newer radical scholarship is clearly illustrated by their contrasting interpretations of Secretary of State John Hay’s articulation of a new Open Door policy during the administration of William McKinley in 1898. In a series of notes, Hay warned European leaders that the United States regarded Asia as “open” to U.S. trade and investment, as occasioned by the disintegration of the Chinese state into civil war and the occupation of the country’s regions by European states and Japan. The United States insisted that unfettered access to markets in China be honored—and by implication, that the closing of such markets to U.S. goods might lead to confrontation.

For realists, the Hay “Open Door Notes” illustrated the propensity of policymakers to make threats that far exceeded any likely action. The strategic gap between rhetoric and reality, they argued, had long characterized U.S. foreign policy, from the 1890s to the era of President Woodrow Wilson’s calls for democratization to the vehement stance against the spread of communism expressed by every Cold War president.2

Revisionists such as Williams instead argued that the Open Door Notes presaged the emerging U.S. global imperial vision.3 Hay’s demands that the world respect the country’s right to penetrate economies everywhere would become the guiding standard for the U.S. role in the world.

Some of Williams’s writings seemed to emphasize material reality—the needs of capitalism—and others the beliefs held by elites, namely the overriding necessity of new markets. Among the revisionist school of historians, which also included Lloyd Gardner, Gar Alperowitz, and Thomas Paterson, was Gabriel Kolko, author of The Politics of War and, with Joyce Kolko, The Limits of Power: United States Foreign Policy from 1945 to 1954.4 In these volumes, the authors laid out in more graphic and precise terms the material underpinnings of U.S. Cold War policy. The Kolkos emphasized the material and ideological menace that international communism, particularly the example of the Soviet Union and popular Communist parties in the third world, represented to the construction of a global capitalist empire after the Second World War.

For the Kolkos and other revisionists, the expansion of socialism constituted a global threat to capital accumulation. With the end of the Second World War, there were widespread fears that the decline in wartime demand for U.S. products would bring economic stagnation and a return to the depression of the 1930s. The Marshall Plan, lauded as a humanitarian program for the rebuilding of war-torn Europe, was at its base a program to increase demand and secure markets for U.S. products. With the specter of an international communist threat, military spending, another source of demand, would likewise help retain customers, including the U.S. government itself. The idea of empire, which Williams so stressed, was underscored by the materiality of capitalist dynamics.

The historical revisionists thus introduced a political-economic approach to the study of foreign policy. This frame emphasized different factors shaping U.S. global behavior than did those that singularly emphasized national security. The realists referred to human nature and the inevitable attributes of state behavior, particularly the pursuit of power. The traditionalists highlighted the threat to security of certain kinds of states, mostly from international communism. For them, the modern international system was driven by a vast ideological contest between free and democratic states and totalitarian ones. Power, security, and anti-communism were together central to understanding U.S. foreign policy, not economic interest.

The revisionist approach emphasized several different components of policy. First, the new historians saw fundamental connections between economics and politics. Whether the theoretical starting point was Adam Smith or Karl Marx, they looked to the underlying dynamics, needs, and goals of the economic system as sources of policy. These writers began from the assumption that economic interest infused political systems and international relations.

While the realists acknowledged economic interest as a factor of some importance to policy-making, it was considered merely one of a multiplicity of variables shaping international behavior. By contrast, revisionists argued that while the forces of security, ideology, elite personalities, and even “human nature” had some role to play, all were influenced in the end by economic imperatives. The behavior of dominant nation-states from the seventeenth through the twentieth century involved trade, investment, financial speculation, the pursuit of slave or cheap labor, and access to natural resources. The pursuit of economic gain drove the system of international relations, and while sometimes this required cooperation, at other times it necessitated war, conquest, and colonization.

The revisionists made a further innovation at the level of discourse: during the Cold War, the mere mention of the word “capitalism” signaled that the user was a Marxist. Consequently, without naming the economic system, any hope of analyzing its relation to politics and policy was foreclosed. And that meant ignoring the possible relevance of the dominant economic system from the fifteenth century on. But, as has been suggested, some historians and social scientists who employed the political-economic perspective recognized that as an economic system evolved, international relations changed with it. This was so because capitalist enterprises and their supporting states accumulated more and more wealth, expanded at breakneck speed, consolidated both economic and political power, and sometimes built armies to facilitate further growth.

Some historians, borrowing from Marx, studied the evolution of capitalism by analyzing the accumulation of capital and newer forms of the organization of labor. At first, theorists wrote of the rise of capitalism out of feudalism. Marx called this the age of “primitive” or “primary” accumulation, because profit came from the enslavement of peoples, the conquest of territories, and the use of brute force. Subsequently, trade became a significant feature of the new system, and capitalists traversed the globe to sell the products produced by slave and wage labor.

This era of commercial capitalism was dwarfed, however, by the emergence of industrial capitalism. New production techniques developed, particularly factory systems and mass production. The promotion and sale of products in domestic and global markets increased. By the 1870s, the accumulation of capital in products and profits created enormous surpluses in the developed countries. These required new outlets for sale, new ways to put money capital to work, and ever-expanding concentrations of capital in manufacturing and financial institutions. By the mid-twentieth century, some theorists wrote of a new era of “monopoly capitalism,” a global economic system in which most commercial and financial activities were controlled by a small number of multinational corporations and banks.5

The revisionists of the 1960s argued that much of this economic history was ignored entirely by mainstream analyses of international relations. They responded by uncovering the reality of the U.S. role in the world, concentrating on specific cases of links between economics and politics. These included the influence of the country’s largest oil companies on the U.S.-managed overthrow of Mohammed Mosaddegh in Iran in 1953 or the coup in Guatemala in 1954 after president Jacobo Árbenz threatened to nationalize lands owned by the United Fruit Company. And while some revisionists did see the Soviet Union as a security threat to the United States, the broad consensus of the political-economy approach was that socialism as a world force threatened the continued global expansion of capitalism. As the nature of the anti-capitalist forces and challenges in particular countries changed, so too did the needs and tactics of U.S. foreign policy.

The political-economy approach also regarded class structure as central to the understanding of the foreign policy of any nation. Some classes dominate the political system at the expense of others. In capitalist societies, those who own or control the means of production dominate political life.

Therefore, while realists and traditionalists prioritize states as the most important actors in world affairs, political economists see states and classes as inextricably connected. Writers of all schools write about rich and poor states and powerful and weak states. Most, however, stop there. The state is central. Political economists and historical revisionists connected states to classes, and vice versa.

Finally, while revisionist historians worked on the principle that class interest controlled the foreign policy process, they tended to take a “hegemonic” view of that control, leaving little room in their theoretical frame for counterforces of resistance. The resulting analyses often seemed to imply that the United States was omniscient, all-powerful, unbeatable, and unchangeable in its conduct. After the Cuban Revolution and the Vietnam War, however, some analysts began to focus on challenges to U.S. hegemony around the world, especially in the global South. However, in the main, the historical revisionists developed a top-down understanding of international relations. Much of the anti-American ferment in the world, including anticolonial struggles, revolutions, and third world coalition-building, received insufficient attention.

The Revisionist Legacy

Although that hegemony has been weakened, the traditional ways of studying international relations in the United States remain influential. Many studies are ahistorical, atomizing political reality while marginalizing the causal role of economics, and ignoring the effect of class interests in the making of foreign policy. The old enemy, international communism, is gone, but a new one, international terrorism, has taken its place. And like their Cold War precursors, mainstream theorists of international relations normalize war, regime change, and an ever-expanding military and security state.

Hegemonic thinking during the Vietnam era was questioned by scholars who challenged professional barriers and ideological taboos. Social movements demanded new thinking about world affairs. And scholar-activists began to revisit the work of maligned theorists such as Marx and V. I. Lenin. Historical curiosity increasingly led them to ask not only what happened, but why. Breaking through hegemonic ideas remains a vital task today.

Notes

- ↩An old but still compelling history of U.S. labor struggles and anti-communism in the early years of the Cold War can be found in Richard O. Boyer and Herbert M. Morais, Labor’s Untold Story (New York: United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America, 1955).

- ↩See George F. Kennan, American Diplomacy, 1900–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969).

- ↩William Appleman Williams, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy (New York: Delta, 1962).

- ↩Lloyd C. Gardner, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and Hans J. Morgenthau, The Origins of the Cold War (Waltham, MA: Genn, 1970); Gar Alperowitz, Atomic Diplomacy (New York: Vintage, 1965); Thomas G. Paterson, Soviet-American Confrontation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973); Gabriel Kolko, The Roots of American Foreign Policy (Boston: Beacon, 1969) and The Politics of War (New York: Vintage, 1968); Joyce Kolko and Gabriel Kolko, The Limits of Power (New York: Harper, 1972).

- ↩Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, Monopoly Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966).