Harry Targ

(a repost)

And

at college after college in recent years, students have rallied to block

appearances by speakers whose views don’t jibe with current campus orthodoxy.

Most of those speakers are conservatives. (Rem Rieder,

“Campuses Need First Amendment Training,” USA

Today-Journal and Courier, November 29, 2015, 8B).

Stories about academic freedom and free speech have

been appearing in newspapers more frequently over the last few weeks. And

curiously enough political actors on and off campus who traditionally have been

least likely to be concerned about these subjects are becoming its major

advocates.

Historically, universities, like most institutions

in society, have been designed by and served the interests of the dominant

powers. Higher education in the United States from the seventeenth century

until the civil war educated theologians and lawyers to take leading positions

in the political and economic system. As the nation was transformed by the

industrial revolution, universities became training grounds and research tools

for the rise of modern capitalism. Young people, to advance the needs of a

modern economic system, were educated to be scientists, engineers, mathematicians,

and managers. Economists were produced to develop theories that justified the

essential features of capitalism.

After the rise of the United States as a world power

in the 1890s, higher education increasingly included studies of international relations,

weapons systems, and the particular mission of powerful nations in the world. In sum, the historical function of the American

university since the 1860s has been to mobilize knowledge and trained personnel

to service a modern economy and a global political power.

The conception of the university articulated by

intellectuals through the centuries, however, also implied an intellectual

space where ideas about scientific truths, engineering possibilities, ethical

systems, the products of culture, and societal ideals would be discussed and

debated. During various periods in United States history, during and after the

Spanish-American War, the Progressive era, World War I and its aftermath, the

Great Depression, and the Vietnam War era, for example, the university became

the site for intellectual contestation. But during most periods of United

States history unpopular ideas introduced in the academy by faculty or students

were subject to repression, firings of faculty, and expulsion of students. This

was particularly true during World War I and the depths of the Cold War in the 1940s and 1950s.

It was out of the many forms of repression that

faculty and student associations advocated for the idea of academic freedom.

Articulated by philosopher John Dewey early in the twentieth century and

formalized by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), the

principle, not the practice, was enshrined in official statements by both

university administrators and faculty.

Despite the broadly endorsed tradition faculty were

purged from universities during the 1940s and 1950s, not primarily because of

their teaching and research activities, but because of alleged political

associations off campus. Others were fired or did not have contracts renewed

because their teaching and research challenged reigning orthodoxies about

economics, politics, and war and peace. In the 1960s, universities sought to

restrict the free speech rights of students as well.

For a time as a result of the tumult of the 1960s,

universities began to provide more space for competing ideas, theories,

approaches to education, and allowed for some discussion of fundamental

societal problems including class exploitation, racism, sexism, homophobia, and

long-term environmental devastation.

But by the 1990s, reaction against the expanded

meaning of academic freedom set in. The National Association of Scholars was

created by political conservatives to challenge the new openness in scholarship

and debate on campus. Right-wing foundations funded David Horowitz to launch a

systematic attack on faculty deemed “dangerous.” Horowitz unsuccessfully tried

to organize students to lobby state legislators to establish rules impinging on

university prerogatives as to hiring of faculty and curricula. Politicians

targeted scholars deemed most threatening including such noted researchers and

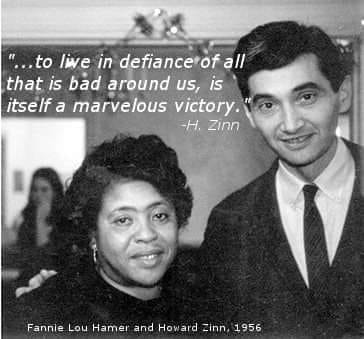

teachers as Howard Zinn, William Ayres, Ward Churchill, and Judith Butler. The

attacks of the last decade were based more on the ideas which “dangerous”

professors articulated than their associations.

Since the upsurge in police violence against African

Americans and terrorist attacks on Planned Parenthood, and rising Islamophobia

and homophobia, a new generation of student activists has emerged challenging

violence, racism, sexism, and homophobia. Students have protested against police

shootings everywhere and they have linked the general increase in violence and

racism to the indignities they suffer on their own campuses.

In response to the events at the University of

Missouri, student activists around the country have brought demands to

administrators challenging the many manifestations of racism and other

indignities experienced at their schools. The response at almost all colleges

and universities has not been to address the demands raised by students but

instead to change the discourse from the

original issues to the protection of academic freedom and free speech. In

other words, university administrators and media pundits, as the quote above

suggests, have swept student complaints under the rug and have used the

time-honored defense of academic freedom and free speech to ignore the reality

of racism, sexism, and homophobia. The defense of free speech has become a

smokescreen.

Academic freedom and free speech must be defended.

But it must be understood that today those who most loudly defend them are

doing so to avoid addressing the critical issues around class, race, gender,

homophobia, and violence that grip the nation and the world.

(For a more detailed rendition of political repression

in higher education see Harry Targ, “Red Scares in Higher Education:

Reinventing the Narrative of Academic Freedom,” www.heartlandradical.blogspot.com,

May 21, 2015.)